Running your own services on your SOHO router for the greater good

Published on . Last updated on

Contents

Recently, I’ve been wanting to run a PiHole server for ad-blocking in my home network, but I didn’t want to set up a machine exclusively for it. So, I thought I could reuse a Raspberry Pi 4 that is running OctoPrint for a PiHole setup. This worked fine for the most part, but I wasn’t fan of the setup for a couple of reasons:

- The RPi4 is hooked up to the network over WiFi. Ideally, the recursive DNS resolver that my entire home network will be using should not have a lot of latency, and I would rather not have it be on a WiFi connected node since most of our personal devices at home are also on WiFi.

- I don’t keep the RPi4 running at all times to conserve energy, but I would have to if I’m going to run a DNS server on it.

I could live with the above, but can’t one do better? Just run it on the one device that actually has to be always on and is still (hopefully) low power, your WiFi home router!

In this post, I’ll go over how I would generally go about mucking around with SOHO routers and exactly what I did to achieve my goal in this particular instance with the TP-Link Archer C3200.

TL;DR

If you have a TP-Link Archer C3200 or a “similar enough model” and you’d like to run your own tools/services on it, follow the instructions in this GitHub repository.

Setup

The WiFi router we have is a TP-Link Archer C3200 which we got on sale a couple of years ago. It is not exactly a great starting point if you’d like to run any other piece of software the vendor didn’t want you to. The vendor simply does not allow you to execute your own code. There is some access to the device over Telnet but that is highly limited and presents configuration options that are available in the web UI anyway. SSH is listening and accepts connections, and you can login, but you cannot actually get a shell session or execute any commands..

No biggie, one could usually get around these limitations by changing their device’s firmware to an open source alternative like OpenWRT or DD-WRT. However, as it is becoming the norm for SOHO routers, none of these projects have any builds available for the TP-Link Archer C3200. That’s because well, the vendor locked the device down even further and it would only accept signed and authenticated firmware from the vendor.

Ah well, none of this is surprising and is actually standard fare for pretty much every cheap - if you consider $100+ cheap - consumer-grade device out there to my knowledge. So, we’ll just find a “feature” that allows us to do what we want anyway.

Goals

Now that we’re determined to take this route, we have to specify what we’re looking for a little bit better so we don’t end up scope creeping or taking things too far. So here’s what we, as well as this article, will constrain ourselves to:

- Finding a persistable code/command execution “feature”. It doesn’t have to be remote, but it has to be automatically triggerable on device startup.

- Identifying a suitable persistent storage option for binaries for the device. This could really be anything, and it would vary quite a lot from device to another, what we’re looking for here is ideally simple and limited to the device itself without any external dependencies.

Additionally, to make this project a bit more approachable and interesting, I decided to try to scope the project to software as much as possible; hence no mucking around with the hardware unless necessary.

Information gathering

First order of business is get a copy of the firmware, usually in some binary format, which we can dissect to try and do a plethora of things:

- Get an idea for how the software side is put together, so what kind of software does the device run, and more importantly, can we use it for our purposes?

- Find default keys or passwords for services like SSH and/or telnet (cough backdoors cough)

- Get our grubby hands on some executables that we can reverse engineer for more information or to find vulnerabilities that we could exploit

The list goes on and on, you get it.

Luckily, I won’t have to open up the device to get the firmware binary since it’s available for download from the vendor’s website. We’ll grab ourselves a copy of the latest firmware and find the desired binary blob inside the zip file next to the manual that we’ll never touch. At this point, the usual procedure I would go through is to run binwalk, extract bootloaders/filesystems/whatever and pray that there is no annoying, weird obfuscation. As luck would have it again, there’s a very obvious squashfs filesystem that binwalk + sasquatch extracted without a hitch.

$ binwalk -e "Archer_C3200v1_0.9.1_0.1_up_boot(160712)_201

6-07-12_15.24.12.bin"

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

115204 0x1C204 LZMA compressed data, properties: 0x5D, dictionary size: 65536 bytes, uncompressed size: 268788 bytes

263168 0x40400 LZMA compressed data, properties: 0x5D, dictionary size: 65536 bytes, uncompressed size: 3658912 bytes

1769984 0x1B0200 Squashfs filesystem, little endian, version 4.0, compression:xz, size: 11220560 bytes, 696 inodes, blocksize: 131072 bytes, created: 2016-07-12 07:22:00

$ ls "_Archer_C3200v1_0.9.1_0.1_up_boot(160712)_2016-07-12_15.24.12.bin.extracted/squashfs-root"

bin dev etc lib linuxrc mnt proc sbin sys tmp usr var web

It won’t always be this smooth, as the firmware may be obfuscated in a variety of ways. That being said, there is always some way to get around it no matter how obfuscated the firmware is. In the worst case scenario, reversing the bootloader should reveal its dirty secrets, but in my experience I never had to go that far. A combination of basic analysis and some hypotheses gets the job done as explained in this /dev/ttyS0 writeup.

Looking for hints on the filesystem

Moving on, we can now have a bit of a look around in the file system, realize it’s a Linux-based device (as they often are), find a couple exectuables and run file on them:

$ file bin/busybox

bin/busybox: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, EABI5 version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib/ld-uClibc.so.0, stripped

Lovely, so now we know that it’s a 32-bit ARM device. It’s also useful to see if there are any kernel modules around:

$ find . -name '*.ko' -type f

./lib/modules/GPL_NetUSB.ko

./lib/modules/ipt_STAT.ko

./lib/modules/kmdir/kernel/crypto/arc4.ko

./lib/modules/kmdir/kernel/crypto/ecb.ko

./lib/modules/kmdir/kernel/drivers/net/ctf/ctf.ko

...

They are one way to easily get some information about the exact kernel version this device runs using modinfo:

$ modinfo ./lib/modules/GPL_NetUSB.ko

filename: /tmp/_Archer_C3200v1_0.9.1_0.1_up_boot(160712)_2016-07-12_15.24.12.bin.extracted/squashfs-root/./lib/modules/GPL_NetUSB.ko

author: KCodes

description: NetUSB module for Linux 2.6 from KCodes.

license: Dual BSD/GPL

depends:

vermagic: 2.6.36.4brcmarm SMP preempt mod_unload ARMv7

Fantastic, now we know it’s running a 2.6.36.4 kernel and an ARMv7 processor. At this point I’ll look around some more in the FS to get an understanding of what’s there and what sort of services to expect, taking notes of them to use later. There is no particular methodology that I follow, but I like to figure out at least the following items:

- As shown above: architecture and kernel version that the device is running

- Default configuration files if available and what they generally relate to

- What kind of services are running and how do they map to executables and configuration?

iptablesconfiguration, so what services are normally accessible and from which networks/interfaces?- For services: are they actually compiled versions of open source tools, and if so what are their versions?

- What accessible services are custom made by the firmware developers or device vendor?

Searching for prior art

Armed with a bit more in depth information about the device, I would usually try to find online resources about the device or “related devices”. One could also search for “related features” like the specific way a certain model has its web UI URLs set up, that could indicate that two different models are using very similar web configuration backends.

In the case of the Archer C3200, there’s quite a few similar models, with very similar names all starting with Archer: Archer C7, C5 and C2300. For some of these models, there are actually rather relevant resources that would prove very useful:

- Wiki and tools for hacking the Archer C2300: https://github.com/acc-/tplink-archer-c2300

- Remote code exec for the Archer C5: https://github.com/JackDoan/TP-Link-ArcherC5-RCE

- Another RCE for the Archer C7: https://www.checkpoint.com/defense/advisories/public/2020/cpai-2020-0338.html/

- A bog-standard command injection in the Archer C2 “Diagnostic” page using the “ping” util: https://pierrekim.github.io/blog/2017-02-09-tplink-c2-and-c20i-vulnerable.html

Reviewing the above, it looks like a huge chunk of our work may already be cut out for us and if not, it looks like there’s quite a bit of potential for exploitation.

As a matter of fact, the same command injection vulnerability in the Archer C2 “Diagnostic” page works on the Archer C3200 firmware version 0.9.1 0.1 v004b.0 Build 160712, which is the latest available version as of the time of writing of this post.

Finding an entrypoint the ole’ fashioned way

It is really nice that an already published vulnerability is still exploitable in another model, but in my limited experience with router exploration, there is quite often a straightforward command injection for some inexplicable reason. In one way or another, the web UI or some other subsystem would have some form of command injection vulnerability, and here are some of the places that are worth taking a look at:

- Like the above, some form of diagnostics page which runs a standard command line tool like

pingortraceroute. - NTP client configuration: most firmware developers don’t want to write their own NTP client for good reasons, but it’s mind-boggling how often NTP clients get daemonized by some vendor-made orchestrator service on the device, and how often these clients are just started with

sprintf’d together configuration and invoked within a shell withsystem. - Logging facilities: for whatever reason, some routers’ firmware invoke

loggerwithin a shell context, and sometimes this is done in an unsanitary way. What do you usually see being logged in the web UI? DHCP leases! What do these sometimes contain? DHCP option 12 - hostname.

And if all else fails, reverse engineering parts of the firmware and bug hunting in the binaries is always an option.

Persistence

We’re quite far already without doing much work, we can already get a shell and run commands over telnet in a similar method to the one described in this advisory. We can even compile and drop other executables if we desire, but this gives us code execution only, not persistence.

“What about the filesystem?” you ask. Indeed, if it were something other than a read-only SquashFS filesystem, that could have worked just fine. However, there are no other filesystems. We could try to figure out how to change the firmware for one of our own choosing, perhaps by finding an issue in the firmware signature checking routine, but it seems a little too far given the current scope and if it were that straightforward I’d expect someone else to have figured it out by then.

Hmm.. this conundrum leads to an obvious question though: how does the device store configuration changes, and can we piggyback onto them?

After a bit of reverse engineering, the answer to “how does the device store configuration changes” is: it does so by utilizing some flash block device, which I didn’t want to muck around with, unless necessary, so I didn’t investigate much further. What we can do instead is use some hints from the Archer C2300 hacking wiki.

It’s not that the systems are similar enough for the same persistence method to work; it’s that the provided scripts are mainly aimed at modifying the configuration files, which is mentioned in other advisories too.

Decoding and encoding backup files

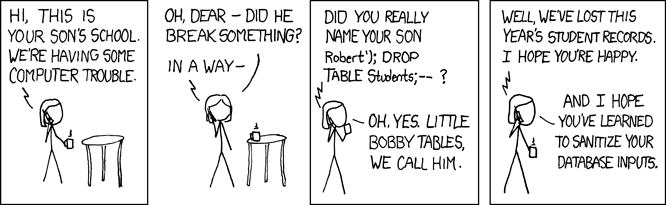

I needed to take a look at the configuration files, and it makes sense: they may contain a few configuration options that are used within shell command invocations without sanitization on startup. After all, it should be already sanitized by whatever system was used to change them, right?

Turns out that threat models matter a bit more in this context. Source: xkcd.

Turns out that threat models matter a bit more in this context. Source: xkcd.

So how do we do so? The files are in some binary format, but the Archer C2300 hacking wiki has some tools for converting the backup .bin files to XML and back. Awesome!

However, they do not work with the Archer C3200 because the format for these files has changed. Surprise!

After spending some time looking around and having tried all the other decryption/decoding tools I could find to no avail, I decided that it was time to start doing some reverse engineering.

Partially reverse engineering the (de-)compression algorithm

I initially went about going through the webserver binaries in Ghidra until I hit libcmm.so and libcutil.so, which are a couple of shared libraries that implement a decent chunk of functionality used by a few subsystems.

libcmm.so contains a couple of interesting functions: rsl_sys_backupCfg and rsl_sys_restoreCfg for dealing with backup and restore, respectively. After going through them briefly, it seems that the encoding process hasn’t changed too much compared to a few other models. The hardcoded DES encryption key used is different, but shows up for other models as well, and the structure is more or less the same for the backup operation:

- Build the backup XML file

- Compress the XML file using proprietary compression algorithm

- Encrypt the compressed file with DES under the static hardcoded key

- Compute the MD5 hash of the encrypted file

- Output the bin file as the MD5 hash of the encrypted file, followed by the encrypted file itself

Looking at the suboperations, it kind of doesn’t make sense that the tools identified so far don’t work after changing the hardcoded DES key to match that of the C3200. In fact, out of the main significant suboperations, only the compression algorithm seems to be the likely candidate for change since everything else is supposedly standard. It’s implemented in libcutil.so as cen_compressBuff and cen_uncompressBuff, so we’ll go ahead and reverse engineer them.

Or.. maybe not. I don’t know about you, but I don’t like doing more work than necessary when it isn’t inherently interesting, so I took a break from trying to reverse engineer them and looked up the function names in hopes of finding some more information.

And for cen_uncompressBuff, I hit a couple of jackpots:

- Tools and information for mucking about with the TP-Link TD-W9970 and TD-W9980 routers, including a method for command execution on startup through configuration files!

- A rather concerning but fantastic write up about a full-blown unauthenticated root shell vulnerability chain on the TP-Link TL-WR902AC

Aand we basically have everything we need! After comparing the cen_uncompressBuff function in Ghidra with the implementation in the tpconf_bin_xml repository, it was easy to identify the small change in the algorithm. However, the corresponding cen_compressBuff changes did not work.

Emulating the compression algorithm with angr and unicorn

Rather than spend some more time trying to hunt down exactly what’s wrong, I modified the code for emulating cen_uncompressBuff provided in the pwn2learn writeup and used angr with unicorn to emulate cen_compressBuff instead.

It took about 30 minutes from looking at the pwn2learn angr code next to the decompiled cen_compressBuff, to having a working compression routine.

Emulation is definitely a much faster approach than reverse engineering especially when testing things out, but it doesn’t always work out. In this particular case, the function was a great candidate for emulation because it has to be generally independent of the device’s state and it invoked a handful of functions, which in turn were also simple.

The resulting code, along with usage instructions, can be found here.

Putting it all together

Well well, we have a way to execute commands on startup and we can use a usb drive to store our binaries/services/scripts, which is also mounted automatically on startup. We also have all the tools needed to craft configuration file with the startup commands that the device will happily restore for us.

We only have to provide our binaries for the tools that we’d like to use! That, IMHO, comes in varying degrees of “complexity”. It can be as easy as installing the right gcc toolchain from your favorite distro’s package repositories and following a simple writeup. In other cases, it can involve building a cross-compilation toolchain, especially when dealing with slightly more exotic architectures (for whatever reason, armeb/ARM Big Endian is one of them). The process of getting the right toolchain built can be made a lot easier by using buildroot, but is still a bit of a chore. Usually, I find myself sticking to compiling statically against musl libc, since it supports ridiculously old kernels which these devices often come with. Case in point: the Archer C3200 comes with a 2.6.36.4 kernel which was already 6 years old when the device came on the market!

For this particular foray, I wanted to run a blackhole DNS server on the router as an alternative to PiHole. As luck would have it once more, a friend was already working on a simple one in rust! It turns out that statically cross compiling to ARMv7 LE with rust is rather straightforward:

- Install a usable toolchain, on Ubuntu/Debian that would be

gcc-arm-linux-gnueabi - Install rustup and add the

armv7-unknown-linux-musleabitarget - Prepare a cargo config file pointing the linker of the target to the toolchain’s gcc

The last couple of steps above can be done with these bash commands in the root directory of a project that uses cargo:

rustup target add armv7-unknown-linux-musleabi

mkdir .cargo

cat << EOF >> .cargo/config

[target.armv7-unknown-linux-musleabi]

linker = "arm-linux-gnueabi-gcc"

EOF

Then let’s get ourselves a stripped release build (the RUSTFLAGS env variable is to pass the strip binary flag to the linker)

RUSTFLAGS='-C link-arg=-s' cargo build --release --target=armv7-unknown-linux-musleabi

And we end up with a statically compiled binary version of nukedns at target/armv7-unknown-linux-musleabi/release/nukedns

I then prepared a startup script which would launch nukedns, put them along with the denylist.txt on a USB drive and plugged it into the router. After a router reboot and some configuration changes for the DNS servers on the router web interface, I was in the business of NXDOMAINing known advertising domain names on my home network, all without having to run an extra device, and maybe you can too!